World On Fire: the Music of ‘Fallout 3’

Fallout 3 is a unique beast, something taken for granted sometimes. Generally — though not quite universally — adored, the game occupies a peculiar space between continuity and innovation. Inheriting the legacy of an acquired franchise, yet announcing itself to millions of console players, Fallout 3’s soundtrack is crucial to both the game’s atmosphere and its lasting impact. Composer Inon Zur’s ambient work, juxtaposed with the warm, crackling tunes of Galaxy News Radio, provided the perfect accompaniment to the fresh, terrifying possibilities of the Wasteland.

To fully understand the game’s soundtrack, you need to look where it came from. Fallout 3, obviously, exists in the context of the Fallout franchise. Not everyone likes where it wandered after its acquisition by Bethesda, but the continuity in soundtracks between 2 and 3 is unmistakable. Mark Morgan, who composed for Fallout and Fallout 2, said that, ‘The challenge to me was to blend a kind of odd ethnic and industrial sound design into something not only musical, but emotional.’ This is clear to hear if you listen through his two soundtracks. There is something mystical about them, suggestive of a newly discovered planet — vast, hostile, untameable. Morgan’s music feels like an ode to the Wasteland itself; in Fallout 3, Zur uses those ethnic/industrial components to explore the player’s place in it.

The ‘feel’ of Fallout 3 is a commonly cited appeal. A major strength of the game is that it crafts a kind of psychological ambience around its players. The soundtrack explores the human potential of the Capital Wasteland: the likely thoughts, fears, and responses of the player. Talking to IGN in 2008, Zur said he was ‘going for more of the psychological effects rather than describing what’s going on on the screen.’ The soundtrack is generally ambient in nature, but it has an edge that colours the in-game experience. Whereas the nature of Morgan’s music seems synonymous with that of the Wasteland, Zur’s work explores humanity’s place within it. The coarsely mystic undertones remain, but they are overlaid with thematic motifs consistent with the game’s story.

When you tune in to it, the OST is markedly eclectic. There are shades of sci-fi in tracks like “Forgotten” and “Out of Service”, the latter veering into psychological horror territory. The fantastical flights of “Wandering the Wastes” could just as easily make for an Elder Scrolls track as a Fallout one. Visually speaking, Fallout 3 is probably one of the granddaddies of seventh generation gaming’s grey, desaturated dirge, but it certainly doesn’t feel dull when you play it. Like the Capital Wasteland’s post-war society, Zur’s soundtrack sounds as if it’s been pieced together in a rusty laboratory out of god knows what.

This ramshackle character was something Inon Zur wanted. The tie between the old and new world was central to Fallout 3’s world and what he sought to bring to it:

‘I think that the connection between what was before and what they have now, plus the aspiration of what you would want to create in the future, this is what creates the perfect world for Fallout. It’s like in many of the Star Trek movies it feels like it was always this way, there is almost no past. On the contrary, with this game we wanted to create a strong contact to the past and to the roots.’

Some characteristics are particularly pronounced, and they serve as a kind of in-game spectrum. There is an unmistakable militaristic edge to Fallout 3’s soundtrack, tempered by a quietly insistent primeval streak. The power struggles of the Capital Wasteland dictate much of the game’s events, and Zur inserts its dull, groaning march into its ambience. Drum cadences ripple throughout the soundtrack, seldom out of mind. “New World, New Order” models this especially well, tightly regimented and metallic. A grind of deadly machinery pervades the album.

In contrast, tracks like “Fortress” dabble in blowing horns, wedding the rigid order of modern military practice with sounds more suggestive of hunter-gatherer societies. Pan flutes haunt “Ambush” and “Metal on Metal”, while didgeridoos turn up all over the place. The contrast is striking. Dense, rusty industrial beasts rub shoulders with flutes, horns, Greek choruses, and goodness knows what else. I’m almost certain I heard a harpsichord in “Chance to Hit”. Classical and ‘primitive’ sounds recur repeatedly, almost serving as pied pipers for the blundering thunder of modern machinery that ostensibly dominates Zur’s work. “Metal on Metal”, one of the OST’s most powerful tracks, listens like a savage dance between two ages – Bronze and Nuclear.

These kinds of juxtapositions are threaded throughout the game’s soundtrack, though they’re seldom in your face. Zur’s work is, ultimately, ambient. It isn’t strictly meant to be noticed. As he recently put it in an interview with GamesIndustry.biz last May, ‘In video games, you don’t need to hear the music – you need to feel it … you don’t need to notice the music but it needs to be part of the whole experience on an emotional level.’ Agree or not, it’s safe to say Zur’s soundtrack is the furthest thing from intrusive. Instead it drifts, lapping at the listener’s mind just enough to tint his or her experience. For the game’s more overt sounds, the player needs to turn to the wireless.

It’s impossible to talk about Fallout 3’s soundtrack without mentioning Galaxy News Radio. Its cheerful, crackling tunes are a haven for players — tellingly, the GNR Soundtrack has enjoyed much more playtime on YouTube than the OST has — but they also reinforce the same themes explored by Morgan and Zur. The Capital Wasteland is a product of the same world that produced the Ink Spots and Billie Holiday. The songs Three Dog plays are remnants of the same past, one the players themselves share given that the songs are ‘real’. Billie Holiday and Co. didn’t cause the war, obviously (that particular DLC was shelved), but their prevalence creates clear parallels with the ambient soundtrack’s tone. The weapons of Fallout 3’s past salt the earth; its melodies hold up the sky.

The interplay is subtle, but undeniable. It is crucial to Fallout 3’s atmosphere. Concerning video game soundtracks, Inon Zur argues that implementation ‘is as important as the quality of the music itself. At least 50%.’ The OST is constant, unobtrusive, and, most importantly, true to the uncertainty of the player’s position. GNR overlays a sense of certainty paradoxically derived from the pre-war world it so derides. Together they create something really quite special. Exploring the Wasteland is not a leisurely affair, but it is absorbing. Zur’s work sits underneath like a heartbeat, rising to meet the quiet, sublime potential of the Wasteland. Everyone who has played *Fallout 3 *remembers leaving Vault 101 for the first time and realising how alone they really were. I doubt as many remember turning on their radio and learning they had company.

The soundtrack guides moments like that more than is immediately apparent. It’s all about implementation, and for sheer punch this moment unquestionably belongs to Inon Zur:

Both the OST and GNR bolster the theme of humanity’s place in post-war ruin. More of the same? Rebirth? Let’s see. Indeed, the OST track listing almost feels like a spectrum. The further along it gets, the more technology falls away in favour of a smoother, purer sound. And as post-war society develops, further motifs grow out of that. There are elements of blues and folk in “Megaton”. The same is true of the town’s ambient tracks. Zur nods to this, saying that the people of Megaton “are kind of creating a new, wild west world,” planting their flag in a new frontier.

Similarly, “Old Lands, New Frontiers” threatens to swell, to promise something new. It is one of the cleanest pieces in the soundtrack, the absence of brutish technological motifs giving strings, bells, and flutes space to breathe and swell. “City of Ruin” feels like a cleansing. There is something quietly, unstoppably indigenous about the music, like a forest reclaiming a fallen metropolis. Indeed, it’s decidedly cyclical. As the game unfolds, the raw, jangly odes of the OST evolve to resemble the songs on the radio. That which is gone will be reborn.

Building upon the work of Mark Morgan, accompanied by the cheerful ironies of GNR, Inon Zur’s soundtrack is characterised by potential just as much as it is by ruin. It explores the psychology of a true American Wasteland; tainted by the brutality of its past, redeemed by the potential of the future — fragile as that future may be. It is in many respects a model video game soundtrack: not terribly memorable on its own, but essential to an experience that most players will remember for the rest of their lives.

Related Posts

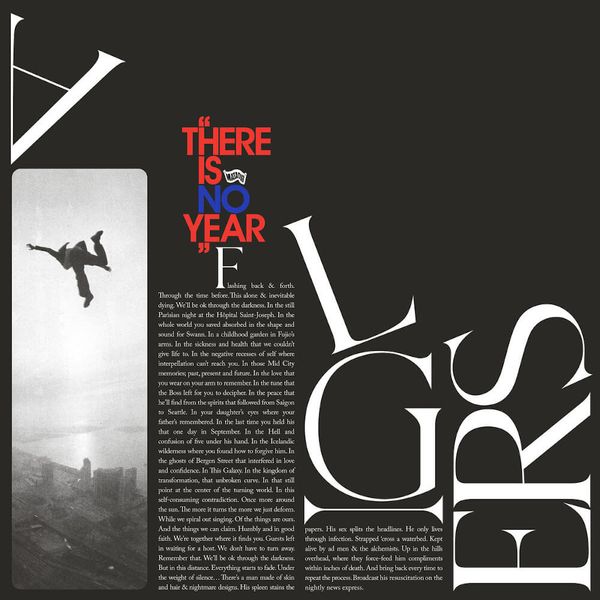

There Is No Year // Algiers

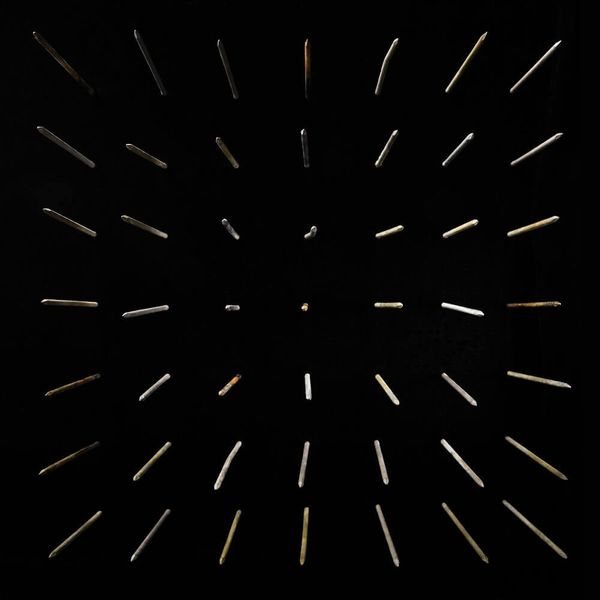

There Existed an Addiction to Blood // clipping.

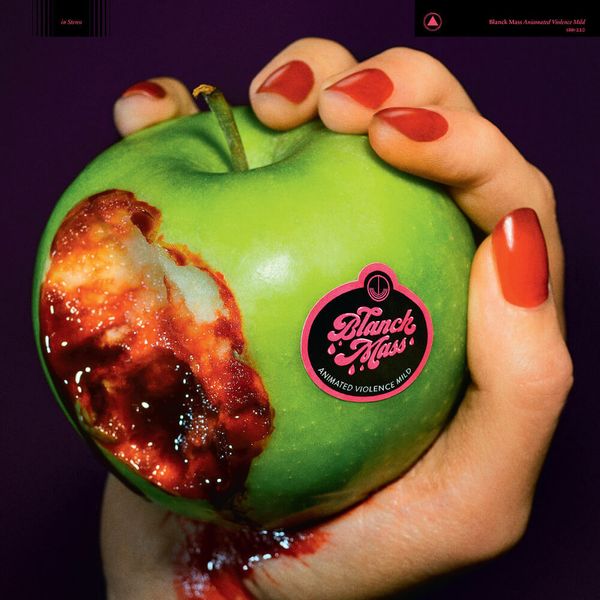

Animated Violence Mild // Blanck Mass