What would a music streaming minimum wage look like?

Music streaming royalty rates are bad for musicians. This is well covered ground, with The Trichordist, NME, Mashable, and plenty of other publications digging into the numbers last year. The long and short of it is artists aren’t even working for pennies these days - they’re working for fractions of pennies. Spotify, the world’s biggest audio streaming platform, is paying out around $3,500 for every million streams. If that doesn’t sound like a lot, that’s because it’s not.

In recent years musicians have had to fall back on touring as their main source of income. Thanks to COVID that’s no longer possible for the foreseeable future, which has helped renew scrutiny on the fairness of existing streaming royalty rates. In the wake of Bob Dylan selling his entire catalog to Universal Music, David Crosby revealed even he can’t support himself based on streaming revenue.

If David Crosby can’t get by one can only wonder how badly smaller artists are struggling. Only, one doesn’t have to imagine. According to the UK Musician’s Union, 34% of musicians are considering abandoning their career, while almost half have already been forced to look for work outside the industry.

Proposed solutions have ranged from music consumers spending more ethically to streaming services upping their rates. With Spotify CEO and prolific non-musician Daniel Ek doing his best Marie Antoinette impression last year by saying artists should just ‘put the work in’ and churn out even more music, not many people are holding their breath on the latter.

Faced with such brazen corporate indifference some are tempted to turn their fury onto consumers, which is seldom fair or productive. Many music listeners have their own pitiful minimum wages to contend with. There comes a point when legislation needs to step in. Huge companies don’t pay minimum wage out of the kindness of their hearts. They pay it because they have to. That’s why it’s there.

Calls are growing for music royalties to get similar treatment. So let’s talk about it.

One cent per stream

According to The Trichordist, on average Spotify pays out $0.00348 per stream. Apple Music pays $0.00675, Tidal $0.00876. For the sake of argument, let’s look at a world in which artists have to be paid one cent per stream. Why? It’s a nice round number for one thing, and it also happens to be one of several demands made by the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW) to Spotify.

UMAW organiser Cody Fitzgerald, a composer based in Brooklyn, New York, says the expectation of minimum payment is no different from any other line of work. ‘A minimum wage is exactly what we’re talking about,’ he says. ‘Artists often aren’t seen as workers, but the fruits of their labour are enjoyed around the world every day. A lot of people can’t live without art, without music.’

Putting aside the fuckery of record labels taking the lion’s share of many artist’s incomes (more on that below), that would multiply streaming income several times over. Apple Music would be paying out almost twice as much, Spotify three times as much, and YouTube six.

Let’s do some quick calculations to see what that might mean in real terms. Though Spotify does not show users play statistics, it does show monthly listeners. Let’s say on average each listener plays ten songs per year and see what that translates to. (Fully appreciate these are back-of-the-envelope calculations and they should be treated as such. If more concrete data was available I’d use it.)

| Members | Annual Spotify listeners | Annual royalties at $0.00348 | Annual royalties at $0.01 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| David Crosby | One | 3,039,636* | $10,577.93 | $30,396.36 |

| Wolf Alice | Four | 16,012,020 | $55,721.83 | $160,120.20 |

| Beak> | Three | 1,097,950 | $3,820.87 | $10,979.50 |

* This is to say nothing of projects like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young ↩

Even those numbers look pretty meagre, but it’s a start. Artists seldom see anywhere near 100% of royalties for their own work (more on this below), but a fraction of around $30,000 is still a lot better than a fraction of around $10,000. It would make stories like this less common, or at least slightly less obscene.

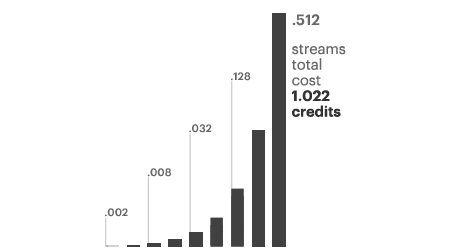

Paying artists more per stream is not a purely hypothetical question. There are platforms already at the cent per play mark — or higher. Resonate is a cooperative founded in 2015. Its ‘stream2own’ model doubles the amount paid to artists each time a song is played until on the ninth play the listener owns it. That way the artist receives just over a dollar per song, roughly equivalent to an iTunes single download. Stream an album enough times and you effectively ‘buy’ it.

Resonate founder Peter Harris started the platform with the intent of bypassing music label/tech company stranglehold, putting money directly into artist’s pockets. ‘The prevailing streaming rates were somewhat arbitrarily set by agreement between various tech companies and the major music labels,’ he says, ‘which negotiated from their position as owners of massive catalogs, not as mediators for individual artists.’

SonStream, a startup based in Stoke-on-Trent, England, pays an average of 2.5 British pence per stream (around 3.3 American cents). On social media the company posts top streams and payout info every week, cheerfully comparing its numbers to Spotify as it does so. Like Resonate, SonStream uses a pay as you go system instead of a subscription model. If a user plays ten songs, they’ll pay around 25p directly to those artists.

As for income, SonStream takes 10% of revenue from all sales. ‘SonStream is just about holding it together by having the licence to around 1,000,000 tracks,’ says founder Seb Clarke, ‘many of which are by niche artists whose supporters are willing to pay a little more for an ethical platform.’ For context, Spotify has more than 60,000,000 songs.

It’s early days, but it is undeniable that a percentage of listeners are happy to drop the convenience of mainstream streaming (mainstreaming?) platforms if it means putting money directly into artists’ pockets. At present subscription money goes directly to the platforms, which then redistribute it as they see fit. If Resonate and SonStream are any indicator, a streaming minimum wage would likely mean rewiring streaming platforms so money goes directly from listeners to artists, with platforms taking a cut as the middleman, a la SonStream.

Would a pay as you go approach be more or less expensive than subscriptions? It largely depends on the number of songs played in a given month. Spotify costs $9.99 per month, so with a cent per play system one could listen to 950 songs a month and still be saving money. ‘The average music fan gets the chance to listen to dramatically less music,’ Clarke says. ‘A “Pay per Play” model like SonStream, even though in theory it charges more per stream, actually costs the average user far, far less. If the user doesn’t play anything, they don’t pay anything.’

The handwringers

Enshrining higher royalty rates in law sounds good, but is it realistic? Spotify famously still operates at a loss after all (partially because it has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on podcast-related acquisitions.) Maybe streaming platforms would love to pay more but simply can’t. Tough luck, artists.

There are a few things to unpack with that line of thinking. First, what the goal is. Is the goal to build a vibrant, sustainable industry in which artists are fairly compensated for their work? Or is the goal to prop up tech monopolies? All too often defences of the status quo seem to be working backwards from the latter.

Second, streaming as a whole is awash with money. Most apologists for the current streaming model salivate over the industry’s growth over the last decade. Revenue topped $20 billion in 2019 and had another good year in 2020 despite a vast majority of musicians eating dirt over the same period of times. The money is there, it just has an uncanny knack of finding its way to those at the top.

A line graph going up doesn’t necessarily mean things are getting better for everyone. More money being made doesn’t necessarily mean everyone is making more money, or that it’s going to the appropriate people. As UMAW’s Cody Fitzgerald puts it, ‘Spotify is a company that has been built off the backs of artists. Artists make everything they do possible.’ Platforms like Patreon usually have the good sense to take a 5-12% cut and keep their mouths shut. The suits at Spotify would do well to follow their example.

The excuses for shady business practices haven’t evolved much over the years. Back in the 1800s child labour laws were resisted by factory owners complained that it would hamper innovation and make their products more expensive. Alas. Sometimes ethical concerns outweigh financial ones, even in rampant capitalist nightmares. If a company can’t function without exploiting its workers maybe that company shouldn’t exist. In most walks of life this is recognised as common sense, but the arts don’t always get the same treatment.

There is also the more reasonable objection that raising rates too much could repel listeners back to piracy, which is what tanked the industry in the first place. Resonate founder Peter Harris believes enough people appreciate music’s value for that to be a worthwhile risk.

‘Let’s suppose there’s an 80/20 rule — 80% are casual listeners who don’t care and 20% are dedicated fans that understand music is art, not content, deserving of adequate compensation. My position is that this was always the case, even before the Internet. So the argument "either we charge $10 a month or return to the dark ages of piracy" simply ignores all of the potential of building services that cater to the audiences that have always supported artists.’

It’s an interesting question. Would it be worth a sizable chunk of the population returning to piracy if those who remained were contributing to fairer royalty rates? I don’t pretend to have the answer here, but do note that services like Netflix and - yes - Spotify have shown people are happy to pay a few dollars a month in exchange for convenience. Given there are already platforms like Resonate and SonStream walking the walk it’s hard to believe a streaming minimum wage simply isn’t possible.

Bricks in the wall

Of course we can’t talk about royalty rates without talking about much, much larger systemic issues in the industry. As Jacobin covered in depth last month, there are plenty to go around. Platforms like Resonate and SonStream have positioned themselves as alternatives. ‘What needs to be understood is that there is an international cartel between the major labels and Spotify and YouTube,’ Seb Clarke says. ‘The huge recording catalogues held by the majors are being used as “loss leaders” for the wider internet machine.’

The pandemic has forced artists to step back and take in just how up against it they are. ‘With COVID it’s even clearer how fucked the current system is,’ says Cody Fitzgerald. A cent per stream doesn’t do artists any good if that extra money is going into the pockets of label executives.

Spotify isn’t actually obliged to pay artists anything - they have to give money to the recording rightsholder, which is usually the record company, and the rightsholder is only obliged to pay the artist 15.1% of the revenue for their own song. This was bumped up from 10.5% in 2018. In a testament to how skewed the overton window is, the big story in the press was the ‘44% raise’, not the fact that a 44% raise on a crumb still only leaves artists with 1.44 crumbs.

UMAW’s campaign is thus as much about raising awareness of industry-wide exploitation as it is about Spotify specifically. Fitzgerald recognises substantive change won’t come until there’s united public pressure:

‘We wanted a demand anyone could agree with. There’s a bigger issue here about whether the streaming system is working at all. This was an action to bring that to the forefront of people’s minds. If we were to say “get rid of Spotify” that wouldn’t connect. Education comes first, explaining what the issues are in terms everyone can appreciate. It’s only then you can move public opinion.’

A world in which a music streaming minimum wage exists is a world in which consumer habits, public pressure, and legislation converge. ‘Legislation doesn’t happen without public pressure,’ Fitzgerald says. ‘The first step couldn’t be going to congress and asking for these changes. It’s much easier to have those conversations when you’ve got a lot of people behind you.’

Then of course there are entrenched forces of the status quo. If history is any indicator first they will ignore the pressure, then fight it with everything they’ve got. ‘Tech companies and the major labels are themselves the obstacles,’ says Peter Harris.

What does this all mean for those of us who care about musicians being fairly? There is no great master plan so much as there are a number of small things that can be done to move the needle towards a fairer industry:

Explore ethical alternatives to Spotify et al. With their pay per play approaches it literally costs pennies to try them out. For those unsure where to start we list a handful of services in this article.

If you can afford it, buy from and support artists you like. Platforms like Patreon and Ampled are good places to start, as well as merch shops. Bandcamp Fridays are also continuing into 2021, so keep an eye out for those.

Make your representatives aware of your principles on the matter. Remind them of the political cost of those principles being ignored.

Join the increasing number of music unions, collectives, and charities. UMAW, the UK Musicians’ Union, the American Federation of Musicians, and the Music Venue Trust come to mind. Which one(s) depends on your interests and background.

Talk about it. Positive change seldom happens without huge, undeniable public pressure. There is no real substitute for discussing the issues, identifying solutions, and advocating for them.

And again, one would do well to remember berating individuals for their spending habits isn’t going to fix decades-long systemic issues. Being kind, communicative, and organised probably won’t either, but it makes for a far better fight. From recording studios to factories to hospitals, fair pay for fair work is a cause with many more natural allies than enemies.

Related Posts

With music streaming remuneration reform on hiatus, is it the government’s cue to step in?

Artist-friendly music streaming alternatives to Spotify et al.

Soma, Spotify, and the brave new world of music consumption